A fish under a roof. A stick figure without a head. A series of lines that look like a garden rake.

These symbols are part of an entirely undeciphered script from a sophisticated ancient civilization thousands of years old. And they remain an enduring mystery that has sparked heated debates, death threats to researchers, and cash prizes for the coveted answer.

The latest such prize was offered last month by the chief minister of one Indian state: $1 million to anyone who can decode the script of the Indus Valley civilization, which stretched across what is now Pakistan and northern India.

“A really important question about the pre-history of South Asia could potentially be settled if we are able to completely decipher the script,” said Rajesh P. N. Rao, a computer science professor at the University of Washington who has worked on it for more than a decade.

If deciphered, the script could offer a glimpse into a Bronze Age civilization believed to rival ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Some believe this vast domain held millions of people, with cities that boasted advanced urban planning, standardized weights and measures, and extensive trade routes.

Perhaps more importantly, it might help answer fundamental questions about who the Indus Valley people and their descendants were – a politically fraught debate about the disputed roots of modern India and its indigenous inhabitants.

“Whichever group is trying to claim that civilization would get to claim that they were among the first to have urban planning, this amazing trade, and they were navigating seas to do global trade,” Rao said.

“It has a lot of cachet if you can claim that, ‘Those were our people who were doing that.’”

Why is it so hard to decipher?

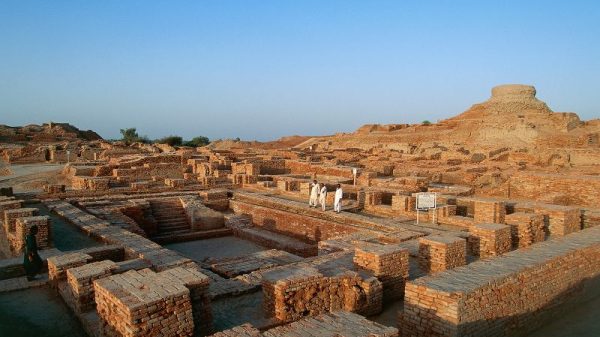

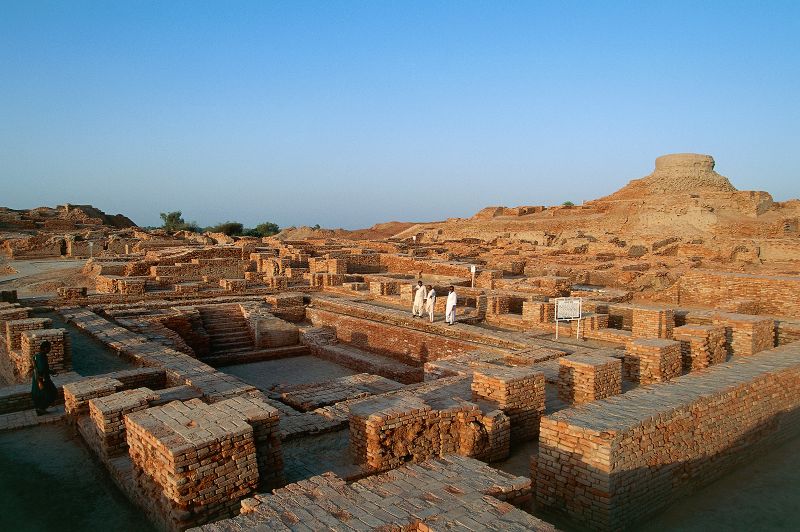

Though the script has remained unsolved since its earliest samples were published in 1875, we do know a little about Indus Valley culture itself – thanks to archaeological excavations of major cities like Mohenjo-daro, located in what is now Pakistan’s Sindh province, about 510 kilometers (317 miles) northeast of Karachi.

These cities were designed along a grid system like New York City or Barcelona, and were equipped with drainage and water management systems – features which at that point were “unparalleled in history,” one paper said.

Throughout the second and third millennia BC, Indus merchants traded with people across the Persian Gulf and the Middle East, their ships bringing copper ingots, pearls, spices and ivory. They crafted gold and silver jewelry, and built faraway settlements and colonies.

Eventually around 1800 BC – still more than 1,000 years before the birth of ancient Rome – the civilization collapsed and people migrated to smaller villages. Some believe climate change was the driving factor, with evidence of long droughts, shifting temperatures, and unpredictable rainfall that could have damaged agriculture in those final few centuries.

But what we know about the Indus civilization is limited compared with the wealth of information available about its contemporaries, such as ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Maya. That is largely because of the undeciphered script, which was found on artifacts such as pottery and stone seals.

There are a few reasons it’s been so hard to decode. First, there aren’t that many artifacts to analyze – archaeologists have only found about 4,000 inscriptions, compared with an estimated 5 million words available in ancient Egyptian, which includes hieroglyphics and other variants.

Many of those Indus relics are very small, often stone seals measuring one square inch – meaning the script on them is short, most sequences containing only four or five symbols.

Crucially, there isn’t yet a bilingual artifact containing both the Indus Valley script and its translation into another language, as the Rosetta Stone does for ancient Egyptian and ancient Greek. And we don’t have clues such as names of recognized Indus rulers that could help crack the script – the way the names of Cleopatra and Ptolemy helped decipher ancient Egyptian.

There are some things that experts largely agree on. Most believe the script was written from right to left, and many speculate it was used for both religious and economic purposes, such as marking items for trade. There are even some interpretations of signs that multiple experts agree on – a headless stick figure representing a person, for instance.

However, until a Rosetta Stone equivalent is found, these remain unproven theories. “No unanimity has been reached even on the basic issues,” wrote Indus experts Jagat Pati Joshi and Asko Parpola in a 1987 book that catalogued hundreds of seals and inscriptions.

Even decades later, “not a single sign is deciphered yet,” said Nisha Yadav, a researcher at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Mumbai, who worked with Rao on the project and has studied the script for nearly 20 years.

Controversial theories

For some people, solving the script isn’t just about intellectual curiosity or academic study – it’s a high-stakes existential question.

That’s because they believe it could settle the controversy of who exactly the Indus people were, and which way migration flowed, in or out of India.

There are two main groups vying to claim the Indus civilization. One group argues the script has links to Indo-European languages such as ancient Sanskrit, which spawned many languages now spoken across northern India.

Most scholars believe Aryan migrants from Central Asia brought Indo-European languages to India. But this group argues it was the other way around – that Sanskrit and its relatives originated in the Indus Valley civilization and spread out toward Europe, said Rao.

He described their claim as: “Everything was within India to begin with … Nothing came from outside.”

Then there’s a second group that believes the script is linked to the Dravidian language family now largely spoken across South India – suggesting Dravidian languages were there first, widely spoken across the region before being pushed out by the arrival of Aryans in the north.

M. K. Stalin, the southern Tamil Nadu state leader offering the $1 million prize, is among those who believe the Indus language was a Dravidian ancestor – which Rao described as the more “traditional” theory, though there are respected scholars on both sides.

Then there are some like Indus expert Iravatham Mahadevan, who argued there’s little point in the debate since the distinction between northern Aryans and southern Dravidians isn’t clear anyway.

“There are no Dravidian people or Aryan people – just like both Pakistanis and Indians are racially very similar,” he said in a 1998 interview.

“We are both the product of a very long period of intermarriage, there have been migrations … You cannot now racially segregate any element of the Indian population.”

Still, the question is fraught. In a 2011 TED Talk, Rao said he received hate mail after publishing some of his findings. Other researchers have described receiving death threats – including Steve Farmer, who along with his colleagues stunned the academic world in 2004 by arguing the Indus script doesn’t represent a language at all, but is merely a set of symbols like those we’d see on modern traffic signs.

How they’re trying to crack it

Despite these tensions, the script has long enamored researchers and amateur enthusiasts, with some dedicating their careers to the conundrum.

Some, like Parpola – one of the eminent experts in the field – have tried figuring out the meaning behind certain signs. For instance, he suggests, in many Dravidian languages the words for “fish” and “star” sound the same, and stars were often used to symbolize deities in other ancient scripts – so Indus symbols that look like fish might represent gods.

Other researchers, like Rao and Yadav, are more focused on finding patterns within the script. To do this, they train computer models to analyze a string of signs – then take away certain signs until the computer can accurately guess what the missing symbols are.

This is useful for several reasons: We can better understand patterns in how the script works – like how the letter “Q” is most often followed by “U” in English – and it can help researchers fill in the gaps for artifacts with damaged or missing signs.

Significantly, knowing these common patterns can help identify sequences that don’t follow the rules. Yadav pointed to seals found in West Asia, far from the Indus Valley; while they used the same Indus signs, they followed entirely different patterns, suggesting the script may have evolved to be used across different languages, similar to the Latin alphabet.

Then there are your average Joes, fans of the puzzle who want to try their hand at solving it. With the announcement of the $1 million prize – though no clear information about where people can apply for it – amateurs have flocked to experts to eagerly share their theories.

“I used to get about one or two emails a week. But now, after the prize was sent out, I pretty much get emails every day,” Rao said. They come from all sorts of people around the world, writing in different languages – with even families working on the puzzle together.

After so many years, Rao swings between optimism and resignation. Any further breakthrough would require international multi-disciplinary teamwork, massive funding, and even political negotiations to allow excavations in border areas disputed by India and Pakistan, he said.

But on good days, he’s still hopeful. So is Yadav, who has been fascinated by the Indus Valley civilization since learning about in the fourth grade. Even without the promise of a solution, the beauty of the task draws her back year after year.

“I look forward to working on the problem every day,” she said. “If we decipher the script, it will open a window into the lives and ideology of Indus people. We will get to know a lot of things about our ancestors … what they were thinking, what were they focused on?”

These details are “just hiding from us today,” she added. “That keeps me glued to the problem rather than anything else.”